After the uprisings of 2020, many in California thought it was time to face up against the state’s notoriously racist criminal justice system. Communities and advocates took aim at the STEP (Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention) Act, a law passed in 1988 which allowed the application of ‘gang’ enhancements to provide extra punishment for those categorized as gang members with enhancements adding 20 years or even a life sentence on top of the underlying charge. With police officers charged with making determinations on who is a gang member, law enforcement gained a tool which allowed them to put people behind bars for decades, expanding their surveillance and punitive power. The use of gang enhancements is part of the three-pronged approach that constitutes the State’s gang policy which, under the cover of law, suppresses and harasses exclusively groups of black/brown individuals in working class neighborhoods through special police units, creates extreme sentencing schemes which treats minor felony offenses as potential life sentence offenses, and institutes intense supervision conditions which restricts one’s ability to reconnect with their community and creates an resource scarce environment where staying in line with the law is an uphill battle. These strategies produced years of unaccountable and violent gang cops, racially-targeted stops, framing cultural markers and religious imagery of racial minorities as evidence of gang membership and inherently criminal, and targeting youth because of a family member’s incarceration history. The gang enhancement has created generational harm, creating an acquired fear that men old and young from Black/Brown communities gained through their powerlessness to fight this intense police scrutiny.

Gang/Racial enhancements in action: 3 decades of racist sentencing practices uncovered

The legal definition of a gang is broadly defined as “an ongoing organization of 3 or more persons, with a common name, or identifying mark or symbol.” Architects of the enhancements claim it has no racialized intent, but why is it that enforcement shows at least 97% of those convicted are non-white? While the definition is so overbroad to potentially include many organizations, the silent identification markers that open certain people up to gang enforcement are cultural and religious markers, youth culture/clothing, and the color of their skin. By its very design, the criminal legal system isolates individuals convicted of felonies, denying them certain citizenship rights and subjecting them to supervision. Those convicted of gang enhancements constitute another legal underclass, denied all the same rights as those convicted of felonies, but with increased racialized stigma and supervision. Oftentimes, per their ‘gang conditions’ they cannot return to the neighborhood they grew up in, they cannot associate with similarly criminalized family & friends, must register as a gang member with the local police and open themselves up to increased supervision by police, all the while checking in with parole. If they fail at any one of these or slip up just one time, they will go back to prison.

The late LA rapper Drakeo the Ruler, who himself twice beat murder charges prejudiced with gang allegations, pointed out how plea bargains factor into mass incarceration and how gang enhancements seek to trump up minor allegations into a life offense.

“Most people don’t realize that many people plead guilty to gang enhancements because they’re offered the chance to go home based on time served. You think that if you take a gang enhancement it’s okay, but if you get arrested again, an otherwise petty charge becomes extremely serious. You can’t say you are not a gang member now because you’ve already admitted that you were… the maximum sentence for intimidating a witness is two to three years – which ends up being about 16 months with half time. With a gang enhancement, you could potentially be facing life in prison.”[1]

As a result of media coverage of Drakeo’s case and overpowering grassroots advocacy from community members just like him, former DA Jackie Lacey was ousted in favor of George Gascon. One of Gascon’s first moves was refusing to charge gun and gang enhancements, reasoning that “gang enhancements too have lead to shocking racial disparities.”[2]

Tides Turn: AB 333 and the beginning of the end for gang suppression

In 2020, the Governor-appointed Committee to Revise the Penal Code released their recommendation to amend the gang enhancement law because it had targeted non-whites for conviction 97% of the time.[3] This recommendation became the basis for AB 333, the bill to reform gang enhancements to deal with the due process violations that had become the norm in

Black/Brown communities since the 1980’s. Through a coalition of partners across the state and despite an opposition desperately bleating about how much communities of color would suffer because of this bill, AB 333 passed the legislature and received its signature from the Governor in November 2021.

AB 333 revises 3 major aspects of the gang law with a number of other changes that clean up some of the overt due process violations that were plain in the law. First, it states that alleged benefit to the gang be ‘more than reputational.” The criteria that a crime has a “more than reputational benefit” ensures that an alleged benefit to a gang isn’t theorized but is proven to be monetary, retribution, etc. Second, it forces the DA to first prove the underlying crime at trial and then conduct another trial that would determine if the underlying conviction was for the benefit of the gang. Determining guilt on the underlying charge prevents gang allegations from muddying the waters and prejudicing the verdict.[4] Finally, the law ensured that the charged offense couldn’t be included in the “pattern on criminal gang activity,” ensuring that the presumption of innocence on the charged offense was returned as a constitutional right after being taken away and denied from people with gang allegations for decades.

Gang enhancements’ role as a prosecutorial weapon against Black/Brown communities was undeniable at the time of AB 333’s passage. Public Records Act requests revealed chilling confirmation of racial disparities from the 2020 statewide data -- many counties had not even convicted a ‘White’ person of a gang enhancement after nearly 34 years and hundreds of convictions.

Quite simply, it wasn’t that the gang enhancement law was being unevenly enforced; it’s that the word ‘gang’ was a stand-in for race. When law enforcement spoke of gang suppression, gang prevention, and gang violence for the past 3 decades, the only types of people California they had in mind to suppress or prevent was young men from Black/Brown communities. When presenting symbols of the ‘gang’ in court, they showed the flag of the United Farm Workers’ Union, they showed a rosary given to someone by their mom, and a 49er’s jersey of a life-long fan. Intentionally and cynically isolated from historical and cultural context, all three of these symbols were used to convict community members of gang allegations.

In Santa Clara County, only 3 people out of 229 convictions were classified as White. A cursory glance at these 3 individuals show that all have Hispanic last names and are alleged to be connected to a Hispanic gang. In 34 years of gang enhancements’ existence, not one White person in Santa Clara County was convicted of a gang offense according to CDCR. In San Mateo County, the results similarly exposed the not-so-hidden racial intent and enforcement of gang laws. The background research established a few basic truths. First, the ‘White’ category contained 4 individuals of Middle Eastern/Western Asian background (all of whom had Hispanic Co-defendants) and misclassified 2 Hispanic individuals as ‘White’. What remained is 3 ‘White’ individuals, 2 of whom are allegedly connected to Hispanic codefendants. There is only 1 individual convicted of a gang enhancement between Santa Clara County and San Mateo County who is ‘White’ and wasn’t charged in association with non-white people. Perhaps the largest indicator of the gang enhancement law’s racist intent and enforcement is that the only population of ‘White’ people convicted of gang crimes in numerous counties are those who grew up in the same Black/Brown neighborhoods and had their associations criminalized.[5]

Reflecting on the data, the arguments on the floor of the California legislature supporting racist gang enhancements which seemed suspect at the time have now been proven wrong. [1] [2] One assembly member took his floor time to block AB 333, stating how helpful the gang enhancement was on cracking down on Neo-Nazis, thus protecting the Black/Brown neighborhoods. This is wrong on two counts: not only do they not target or apply gang enhancements in those situations, the only white individuals who are criminalized are criminalized for their association with black/brown people. I suspect that many counties don’t even have ‘experts’ to testify on White gangs, especially given that all effort for enforcement has fallen on historically segregated neighborhoods in both counties; Eastside San Jose, East Palo Alto, East Menlo Park, North Fair Oaks, San Mateo, Daly City, South San Francisco and a few others. For people we support in these neighborhoods, they often have documented police contact with gang cops that started from 12-13 years old. During a trial we supported with gang allegations, it became clear that even sign-in sheets at the local community centers were being used towards the goal of gang suppression, tracking Black/Brown youth to later allege that the friends they were in the community center with were their fellow gang members. In cases we have supported, this early police contact, oftentimes during childhood, is framed as evidence of gang membership/criminal behavior decades later, rather than illustrating precisely how overpolicing leads to a community where multiple generations are criminalized.

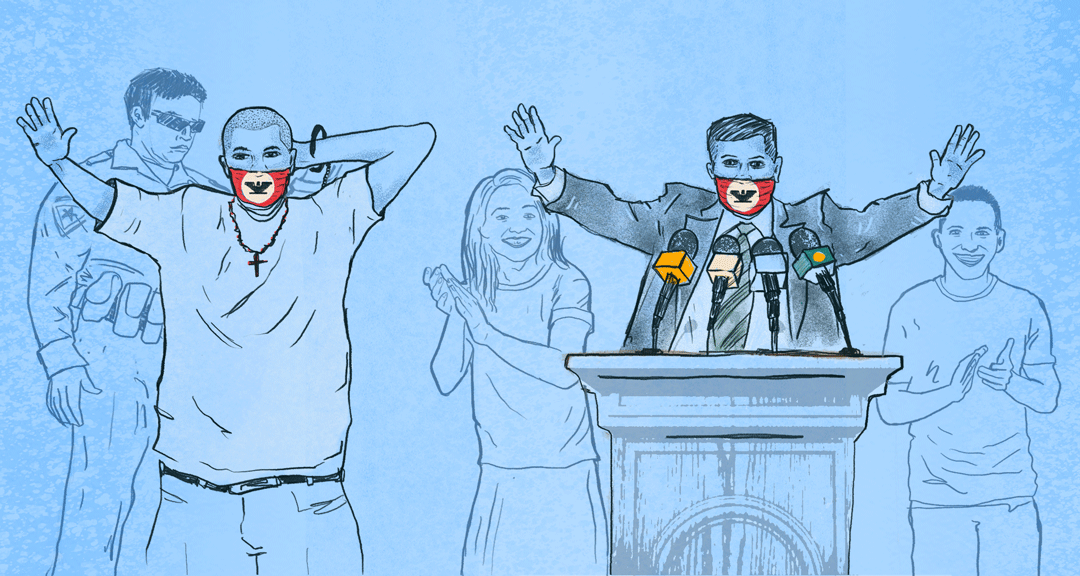

A now infamous, since-deleted Twitter post from former San Jose Police Chief Eddie Garcia encapsulates the racist associations police try to draw, showing firearms and a number of items including a red rosary, red belt, and a mask with the Huelga Bird, the symbol originated by the United Farm Workers’ movement. Any person with grounding in California social movements and without a bias to incarcerate Brown youth understand how the Huelga Bird has spread from inspiration to farm workers fighting against the oppressive farm owners and police to representing the continuous urban and rural struggle of Latinos in America against police repression, poverty, and labor rights. Many Catholic churches give rosaries, often red to represent the blood of the sacrifice, to young people to keep their values and beliefs physically close to them. For Americans, the red stripes on the flag are recognized as the blood of the ancestors who died to establish the county. Wearing an American flag isn’t seen as violent, in fact police officers commonly wear politicized Blue Lives Matter alterations to the American flag in court without the slightest confusion from judges. In this sense, it purposefully selects for youth who are conscious of their history and proud of their peoples’ culture and marks them as worthy of suspicion and potentially dangerous. Of course, this distinction of who can wear the symbol is defined by race, geography, and class. In our arguments on the floor for AB 333, we didn’t expect that a Central Valley legislator who was opposed to the bill would prove our point on how the implementation of the gang law includes the selective enforcement of symbols, setting its sights squarely on young Black/Brown men.

Outreach for the bill took long hours of meeting with representatives which was met with stiff resistance even from those places where cultural symbols of the United Farm Workers’ Union still hold powerful political influence. In a related Assembly floor session, our coalition observed that Assembly Member Dr. Joaquin Arambula was wearing a mask with the symbol originated by the United Farmworkers’ Union but had been resistant to supporting AB 333. Together with Jose Valle, a De-Bug organizer and community expert of Chicano history and culture, and a family of a proud union member who was criminalized for displaying of Huelga Bird, De-Bug penned a letter to Assemblymember Arambula on the history of the symbol and the irreconcilable contradiction he was stuck in.

We hammered on that one contradiction: if the Assembly member was 10-20 years younger, dressed in more casual youthful clothes, and in a criminalized, under-resourced neighborhood only a few blocks from the Capitol, he might be picked off the street, searched without legitimate reason, and forced to fill out a field identification card as an alleged gang member. However, on the floor of the State’s most powerful room, he could wear the Huelga Bird, rightly proud of the history of farmworkers and generational resistance it has represented since then. This is the root of selective enforcement which operates broadly on a policy of racism tempered slightly by class bias which can allow a legislator to be proud of his history, not targeted by racially-charged allegations like those in the community. On the other side of town, a young man victimized by structural failures, underfunded schools, and poverty finds that his attempt at proud resistance to these injustices is met with gang allegations, illegal stops and searches, and increased prison sentences. These narratives rob Brown and Black young men of agency to be political, conveniently granting them just enough agency to be criminals. This accepted racialized framing claims that they are not complex enough to use political symbols and that they are unredeemable, solely because of where they happened to grow up. As organizers, we know that young men harassed by police have some of the clearest understandings of structural failures and, oftentimes, are the ones on the front line to improve their communities, despite the increased risk of incarceration they face. Unfortunately, though we sent the letter, Assemblymember Arambula was conspicuously absent during the vote for AB 333. There is much advocacy from below that must occur in our communities to prevent those from representing us from mindlessly adopting the racial notions handed down by police and district attorneys that justify their surveillance and lead to family separation and prison sentences.

In a midnight hour plea to Governor Newsom before he was set to sign AB 333, the California District Attorneys Association (CDAA) conjured up an unbelievable argument, objecting to a requirement in a previous version of the bill for the alleged gang activity to be ‘organized.’ Though the word ‘organized’ was modified in the final version of the bill, CDAA claimed that including the criteria would “hinder prosecutions against well-established gangs” since California gangs are “unlike the Mafia” and less organized. This makes one wonder: if the requirement that gangs be “organized” would hinder prosecutions against the ‘well-established gangs,’ is there actually any basis to use this enhancement? The DA’s admit this inconvenient fact that “very often, [defendants’ alleged] criminal actions are not even coordinated amongst each other.”[6]

If alleged gangs cannot be proven to be organized or communicating, how is the application of a gang enhancement relevant? Further, how can a gang exist if it cannot be proven to be organized? Isn’t organization a necessary definitional component of any alleged gang activity? Instead of taking a step back and reconsidering their application of gang enhancements as historically over-broad and racist, most DA’s advocate for lower criteria, so they can continue to charge & convict people on gang enhancements that are wholly irrelevant to the facts of the case and prejudice proceedings, enhancing perceptions of guilt.

Gang laws in retreat?

As we look to take advantage of AB 333 and try to right the racial harm of 30 years of suppression in Black/Brown neighborhoods, it’s important to reflect on what has improved and what still must be fought for. The addition that the common benefit to the alleged gang is “more than reputational” is the part of the law that has the most effect of what type of conduct can be charged with a gang enhancement. This change forces the DA to actually find a motive for the alleged crime beyond the asinine logic that has characterized gang prosecution for decades.

Before the law change, a DA could claim that simple possession of a firearm was eligible for a gang enhancement since “carrying a gun benefits Team A in their turf war against Team B, thus it benefits Team A’s reputation to have a gun.” Previously, there was no need to prove intent to use the gun, just superficial evidence of gang involvement like a red hoodie or a 49ers jersey, and the theory that the gun could hypothetically help a gang’s reputation. Absent from their theory or consideration were any of the environmental reasons a young black or brown man from a historically under-resourced, segregated neighborhood might carry a gun – credible fear of harm and trauma from gun violence. After the passage of AB 333, DA’s must prove motive and specific benefit like financial gain or retaliation, not the hypothetical reputational benefit that has added thousands of years to the sentences of almost solely Black/Brown people.

AB 333 is already having an impact in court. Some early reports suggest that DA’s are having trouble finding a solid legal basis for these gang enhancements and some are being thrown out early in the court process. In one case, this data which demonstrates the gang enhancements’ use as a racialized enforcement mechanism has changed the power dynamics and given the DA pause in applying these enhancements. Even better, individuals convicted of gang enhancements on active appeal are being sent back to trial courts to retry the gang allegation with the new criteria under AB 333 constraining the DA’s power on applying enhancements broadly. Those incarcerated individuals returning to court for an unrelated resentencing are buoyed in their demands for retrial or striking the gang enhancement by recent appellate court opinions which affirm the relevance of new legislation, like AB 333, during resentencing hearings. Public defenders and participatory defense hubs in multiple counties have told us anecdotally that the share of gang enhancements they have seen charged in 2022 has decreased noticeably, not likely so much out of sentiment but that they are significantly harder to prove in court with a more reasonable standard to exclude any hypothetical reputational benefit to an alleged gang.

A report published by Santa Clara District Attorney Jeff Rosen on June 9, 2022 seemed to confirm these anecdotes with their own office expecting a decrease in gang prosecutions from 109 cases in 2021 to a projected 33 cases in 2022, which he ties to the “significant new requirements” from AB 333.[7] We know that without the community partially wresting this racial targeted tool away from DA offices thousands of Black/Brown individuals would be subject to extra punishment, proceedings prejudiced by racially-motivated stereotypes about gang members, coercion to plea, intense supervision upon release, and extra attention from special police units.

Past gang suppression and towards something greater

Gang laws should not exist – that much is clear. They are a convenient tool that undermines due process and creates an underclass of only Black/Brown individuals, criminalizing their associations with their peers and creating a scheme where their sentence is doubled, tripled, and quadrupled solely due to their associations and relationships with their community. Unfortunately, Proposition 21 was passed by the voters in 2000, strengthening the gang law and ensuring it would be much harder to dislodge. Without a new statewide proposition, these gang laws will still be on the books. We can take great pride that this reform law and the decades-long practice of race-based ‘gang’ suppression is being weakened year by year as its racist intent and enforcement is exposed for the whole state to see.

[1] https://thelandmag.com/voter-guide/jackie-lacey-drakeo-the-ruler-election/

[2] @GeorgeGascon. “Gang enhancements too have led to shocking racial disparities.

Of the about 11,000 people currently in CA state prisons with a gang enhancement, 92% are Black or Latino.” Twitter, March 4, 2021. https://twitter.com/GeorgeGascon/status/1367567447469920258

[3] Committee on Revision of the Penal Code. Rep. 2020 Annual Report, n.d. 45. http://www.clrc.ca.gov/CRPC/Pub/Reports/CRPC_AR2020.pdf

[4] Yoshino, Erin R. “CALIFORNIA’S CRIMINAL GANG ENHANCEMENTS: LESSONS FROM INTERVIEWS WITH PRACTITIONERS.” USC Gould School of Law, n.d. 140. https://gould.usc.edu/students/journals/rlsj/issues/assets/docs/issue_18/Yoshino_(MACRO2).pdf.

[5] PRA Request: All discharged or non-discharged felons with an offense enhancement of Penal code 186.22(b) or a 186.22(a) conviction from Santa Clara County from October 1, 1988 to January 18, 2022. Per California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Division of Correctional Policy. Research and Internal Oversight Office of Research January 31, 2022.

[6]Greg Totten and Larry Morse, “Cal Matters,” Cal Matters, n.d., https://calmatters.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/CDAA-Veto-Request-AB-333-Kamlager_-002.pdf.

[7] Rosen, Jeff F. Letter to Santa Clara County Public Safety and Justice Committee. “Semi-Annual Countywide Criminal Gang Activity Report,” June 9, 2022. http://sccgov.iqm2.com/Citizens/FileOpen.aspx?Type=1&ID=12784&Inline=True.